A multi-day dryline setup was in place across the central Plains on Sunday, May 8th; and Monday, May 9th, respectively. Observed conditions from radiosonde, or weather balloon, launches, indicated an environment conducive for widespread severe thunderstorms was starting to filter into the central Kansas and central Oklahoma region.

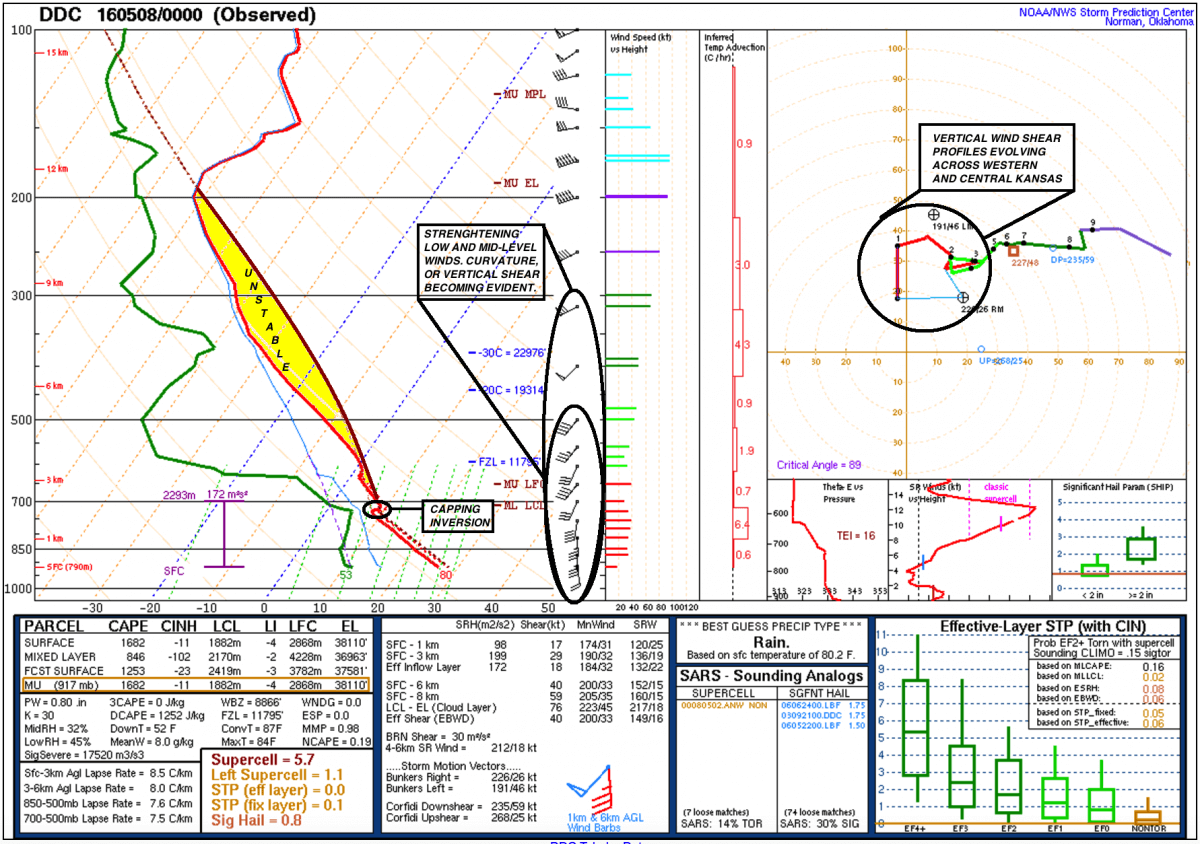

Important to any storm chase is to analyze data the night before of the region you are planning to chase in, as well as the trajectory of where moisture and wind is coming from. In doing so, you can gain an idea of the quantity of moisture you will be dealing with, as well as the rigorousness of any short wave in the upper levels of the atmosphere making its way towards you. Below is the 00z / 7:00pm CDT observed sounding on Saturday, May 7th, the night before the chase. A few key things are pointed out as to the environment that was beginning to develop across the region.

Conditions were ripening the night before our chase, as low-level winds began to curve as evident on the hodograph (polar coordinate graph on the right side of the sounding). There was abundant vertical speed shear between the surface and one kilometer in height, and winds then curved between one and two kilometers. This unveiled prominent low-level wind shear, a necessary “ingredient” for the formation of supercells. Additionally, elevated instability was already in place. Instability is a lifting mechanism for thunderstorms, and is crucial for the evolution of severe thunderstorms.

Early Sunday afternoon, we left the city of Wichita, Kansas, to our target position of Greensburg, Kansas. Moisture was returning rapidly, with dew points nearing the middle 60 degree range across much of central Kansas. Here is a map showing the METARs across the region at 12:07pm CDT.

As we arrived in Greensburg, a well developed cumulus field was in place. The development of supercells was expected within the next few hours after we arrived around 2:30pm CDT on Sunday. There does come a point in time while chasing that models should become second in forecasting. Whereas, looking at current, real-time observations and the sky should be your #1 priority as it can tell you a lot of what is about to happen. The sky is indeed the best tool you can use in this case.

As thunderstorms began to initiate, they would do so in an environment favorable for splitting storms. We meandered on down to Coldwater, Kansas, just to the south of Greensburg, and tracked the storms to the northeast as they were producing golf ball to tennis ball sized hail, and damaging winds. As storms neared Greensburg, it split into a left mover that moved almost due north. The right moving storm continued on to the east-southeast, and we eventually had to make a decision on which storm to chase. We made the decision to drop south down in north-central Oklahoma, where a better thermodynamic environment was in place.

Our decision to travel into north-central Oklahoma paid off, as the storms that split left near Greensburg eventually fizzled out as they entered a more stable airmass. We embarked upon a supercell near Burlington, Oklahoma, that was severe warned for quite some time and was producing tennis ball sized hail. However, the lifted condensation level (LCL; cloud base height) was not able to lower to what was originally thought in the forecast. Therefore, the storm remain rather elevated and was mainly a hail producing storm. We did not see any tornadoes on Sunday. However, storm chasing is not just about seeing tornadoes. In fact, only a small fraction of storms on the entire Earth produce tornadoes. A pronounced inflow tail, or tail cloud, was observed on the supercell as it began to weaken. While it was not the most defined tail cloud, it was quite picturesque nonetheless.

The atmosphere began to stabilize as a result of the “cap”, or lid that suppresses thunderstorm development, did not completely erode as analyzed on observed soundings across the region. Thunderstorms began to collapse and die out rather quickly from their severe levels Sunday night as a result.

Calling the chase, we were treated to a beautiful sunset as well as the sight of the supercells further south in central Oklahoma. The anvil of the supercell was beautifully illuminated, and mammatus clouds were also observed within the anvil.

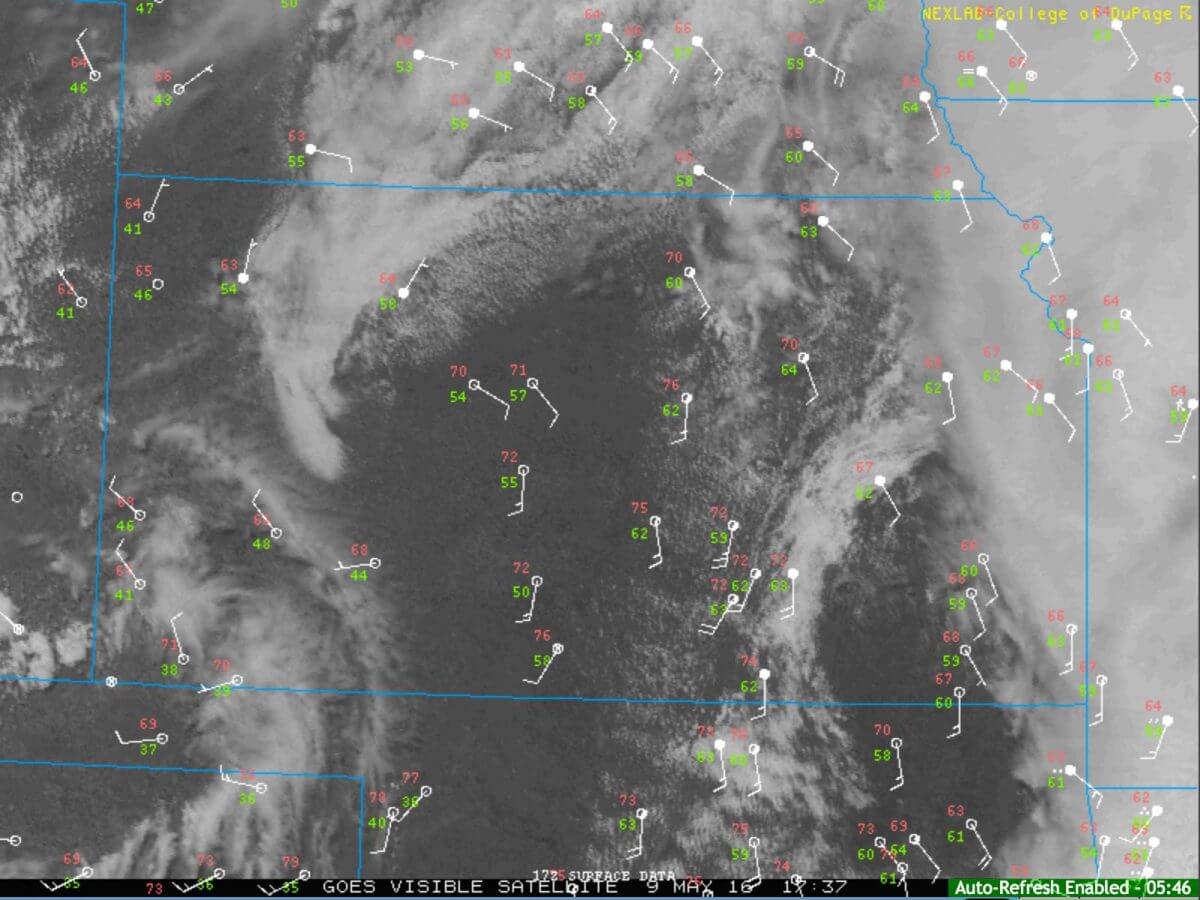

On Monday, May 9th, conditions were once again favorable for severe thunderstorms across the central Plains. Out of position to reach south-central Oklahoma, we decided to play the surface low up in northern Kansas. While the tornado potential was minimal, there was a good potential for large hail events and sporadic damaging winds. A well defined cumulus field was in place Monday afternoon as instability (CAPE) reached upwards of 2,500j/kg, more than enough for severe thunderstorm genesis.

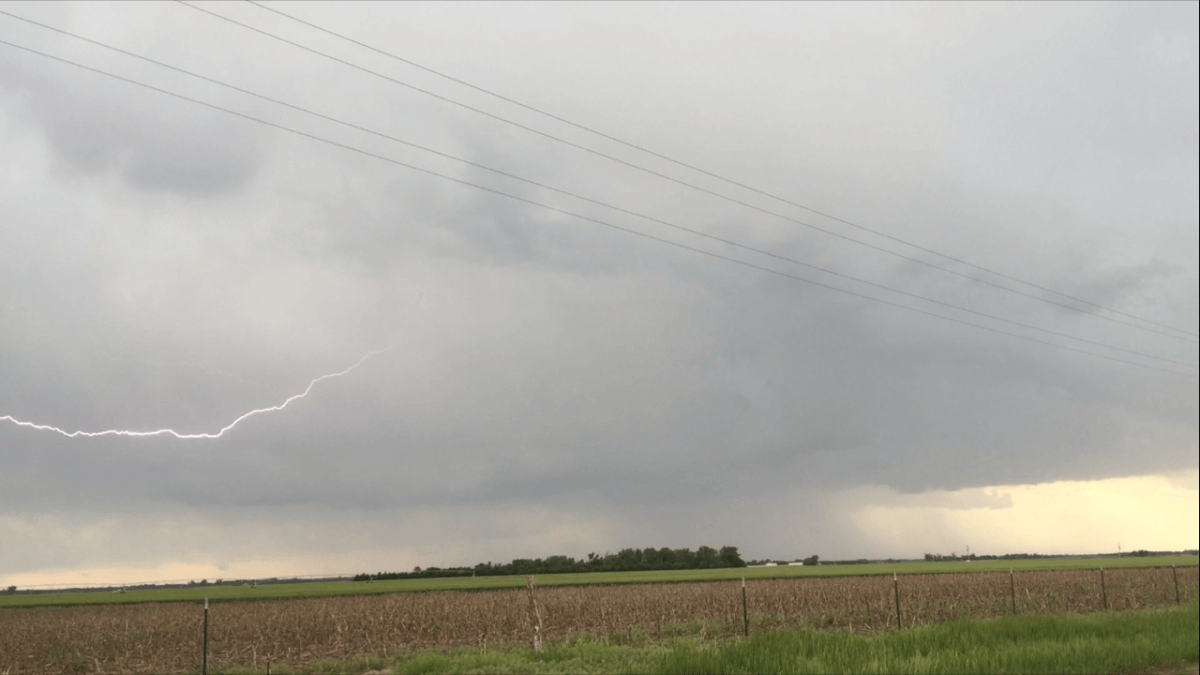

As we moved westward from McPherson County, Kansas, we observed the lowering in the high precipitation supercell. Eventually, we also noticed a wall cloud that was rotating for an ephemeral period. There was frequent intracloud lightning, and a few cloud-to-ground lightning strikes.

This supercell eventually ended up producing half dollar to golf ball sized hail as it moved north-northeast at about 30MPH. The storm began to split, and the left-mover weakened tremendously, so we kept up with the right moving cell as it veered off to the northeast. Trailing behind the storm, we encounter some smaller hail that likely had melted from larger sizes. The sides of the roads were covered in hail, and we observed nickel and dime sized hail.

Storms eventually became linear across eastern Kansas, and produced isolated damaging wind reports across the state, mostly near and south of the Wichita metropolitan area. Other members of our team who dropped south into northern Oklahoma encountered a semi-discrete supercell along the southern tier of the cluster of severe thunderstorms Monday evening. After observing some impressive storm structure, they encountered tennis ball sized hail and unfortunately lost a windshield. As the sun set, the atmosphere stabilized and storms weakened later on in the evening. This was due to a narrow corridor of instability that developed on Monday, as thick stratus clouds lingered in far eastern Kansas and into western Missouri.