This past summer of 2016, I took on a meteorology internship position at KWCH Eyewitness News, an affiliate of CBS, in Wichita, Kansas. Throughout my college education career at Penn State University, I have worked hard at rounding my experience throughout the weather enterprise in as many ways as possible. And, while my ultimate goal is to end up working for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), I wanted to learn how the broadcast sector of meteorology operates. There seemed no better place to accomplish this than in Tornado Alley itself.

Situational awareness is extremely important for operational forecasting, irrespective of your chosen industry — whether you’re a broadcast, aviation, private/commercial enterprise, or government forecaster; you must remain alert to all possible hazards that may present during your shift — particularly if dangerous weather is expected. Additionally, learning how each sector communicates with one another was invaluable, as local National Weather Service offices provide decision support services to local government, news stations via the NWS chat, and critical information received in the private sector is relayed to the NWS. Accurate forecasting with consistent messaging are paramount to building a Weather Ready Nation.

Most people do not think of broadcast meteorologists spending hours behind the scenes performing rigorous data analyses, scrutinizing radar and satellite data, surface and upper-air observations, continuously assessing the never-ending flow of numerical prediction models and their corresponding ensembles, preparing their own forecasts, etc. Gone are the days of ripping the NWS forecast off of the old “weather wire” and regurgitating its content. Modern television meteorologists undergo the same rigorous training in atmospheric physics, fluid dynamics, differential calculus, and computer programming. Forecasts prepared by a television meteorologist will be seen an scrutinized by viewers on all news segments that air throughout the day, from morning rush to the final broadcast of the day — the nightly news (typically 10 pm or 11 pm). In Tornado Alley, including markets such as Oklahoma City and Wichita, severe weather is taken seriously and will take precedence over all other news. If a major severe weather outbreak is forecast, then it is an all-hands-on-deck situation in order to effectively and continuously communicate the potential for dangerous weather.

Read about the history and future of broadcast meteorology

My first day at KWCH was on May 22nd, 2016, the day after the Leoti, Kansas, supercell that produced three tornadoes in western Kansas. Like the 21st of May, May 22nd was shaping up to be another severe weather day across the west-central Plains. So, we got right to work with putting together the short term forecast for the evening across the State of Kansas (which is their entire coverage area), as well as the forecast for the remainder of the week. After the 5:00pm newscast on Sunday, May 22nd, reports of tornadoes in western Kansas started to come in — including a large and violent tornado. The cut-ins into regular programming occurred if there was confirmation of a tornado. Otherwise, cut-ins to regular programming were generally not warranted.

It did get a little tense in the studio at one point on my first day, as the tornado was nearing a few small towns and was rain wrapped. When a tornado is rain wrapped, you cannot see it coming. While the meteorologists were live on camera, I was typing in storm reports into the teleprompter that would scroll across the bottom of the television screen in order to get the reported information out to the public. Personally, I had always wondered how that worked. So, it was quite interesting to be able to do it myself.

After my first few days at KWCH, of which they were all severe weather days, the severe weather pattern began to taper off for a bit by the end of May. Though, persistent heat set in as a strong high pressure system built in over the southern Great Plains. Temperatures were over 100 degrees Fahrenheit for nearly a week straight, in addition to oppressive dew points near or in excess of 80 degrees Fahrenheit. How could we communicate the potential dangers for such high heat indices? I was able to come up with a solution that ended up being quite a hit to the viewers: The Emojicast.

The Emojicast is a chart that shows different icons with respect to the temperature of the dew point. Unlike relative humidity, the dew point is a direct measure of the amount of moisture in the atmosphere (i.e., that part of the atmosphere sampled by the sensor). For our emojicast chart, dew points in the 40-50 degree range resulted in a “thumbs up” icon, as dew points that low are more than comfortable to be outside. As the dew point temperature reached the next 10 degree interval, we adjusted the icon to a facial expression of a smile, then to a worried facial expression, and eventually to a sweltering facial expression for dew points greater than 70°F. Note: An emoji is a digital picture representative of an object, feeling, etc.

The way in which a weather forecast is communicated can make all of the difference when it comes to the public’s understanding, reaction/response, and overall trust. You can have the best forecast in the world, but if it is not effectively communicated, then the forecast loses its merit. Using the emojicast caught the attention of the public to take the heat seriously, and we were quite satisfied with its reach.

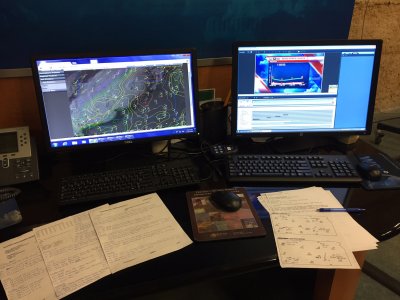

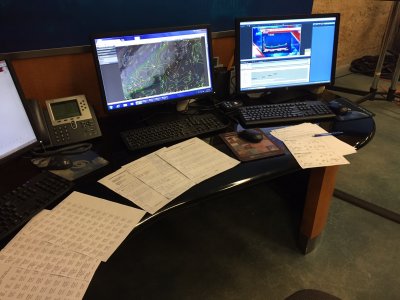

My first task each day, prior to creating any graphical content, was to produce the forecast. I began by focusing on the remainder of the afternoon and evening since there was always something interesting happening somewhere in the viewing area; the rest of the week’s forecast followed thereafter.

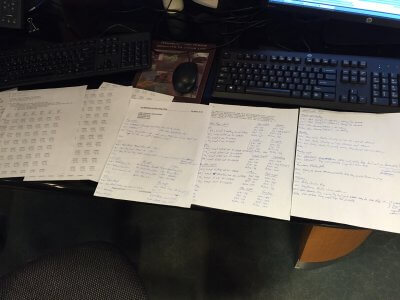

Rigorous note taking of forecast trends and/or anomalies in the operational forecast models, forecast soundings, and other products that were used such as statistical guidance, etc., were written down to make sure there was a consensus on the inter-model and intra-model forecasts (“inter-model” consistency refers to the magnitude of similarity/differences that exist between each of the short- and long-range models; “intra-model” consistency means the same as inter-model, except we are comparing each solution within the same numerical model — for example, how similar are the solutions produced by the North American Model, a.k.a. “NAM”, for each of the past 10 model runs?). A forecaster’s confidence in a particular scenario increases if there is significant model consistency — especially inter-model and for numerous model runs. The models that have been flip-flopping (i.e., inconsistent handling of a disturbance), then the forecaster may discount that model and rely more on those models that have shown better consistency. Sometimes, none of the models are performing well and the forecaster may rely almost exclusively on their own experience with input from the model(s) with a proven track record (some models handle certain meteorological phenomena better than other models — for example, a tropical model will handle tropical waves better than the NAM). Forecaster skills vary, and professional experience is tantamount. A forecaster’s understanding of the atmosphere will always come into play when assessing the past and future propagation of atmospheric features, upper air patterns, fronts (at all levels), low-level boundaries, etc. This was exceptionally crucial given the high variability of upper air patterns in the Great Plains during the late spring and early summer.

When the forecast for the day was all said and done, I compared my forecast notes with the Chief Meteorologist, whom I spent most of my time working with, and we then put the forecast graphics together. The forecast had to be relayed to the public in a matter of roughly 2 to 3 minutes on a regular afternoon and evening newscast. It was quite interesting to see 3 to 4 hours of forecast analysis be condensed into 2 to 3 minutes on camera. There is so much detail involved in forecasting, as you may have seen here with iWeatherNet, but to get the forecast out completely and accurately in such a time constraint of a few minutes can be strenuous. Regardless, it was quite rewarding to see the excellence in our forecasts pan out and to see the verification. Weather, particularly severe weather in the Great Plains, never ceases to amaze me.

At the conclusion of my meteorology internship at KWCH News in Wichita, Kansas, this past summer, I learned how forecasts are communicated on a daily basis at a news station — no matter how volatile the forecast may be. There were a few days that had the potential for significant severe weather, but to relay it to the public in a clean, clear, and concise manner, is exceptionally important in order to get people prepared and not cause panic.

Communication(s) with local emergency management, the National Weather Service, etc., is all done behind the scenes while the viewers see a few minutes of the forecast during on air news segments. Like all meteorologists, broadcast meteorologists are sometimes the ones at the helm during major weather events, and commit hours of analyzing real time data and forecast trends in order to get the forecast out to the public. The value of having the opportunity to learn and work in the broadcast sector of meteorology in Tornado Alley? Priceless.